The catalyst was discovered almost entirely by chance when Robin Hamilton was creating an electrode for an undergraduate student working on a waste biomass upcycling project. He mixed up a combination of powders and allowed them to sit overnight in water, intending to finish the cell the following day. When he returned in the morning, the mixture was bubbling – a reaction that was extremely out of the ordinary.

“It ends up being that when you mix these two things together, they interact, they work together and hydrogen comes off. It floored us,” says Hamilton, a senior research associate in the Department of Chemistry.

Hamilton consulted chemistry professors Jeff Stryker and Jonathan Veinot, sharing the unexpected discovery and drawing on their respective expertise. The team quickly realized they had something remarkable on their hands – the specific combination of powders could serve as a new type of catalyst.

The catalyst they created is made with material that is non-toxic and plentiful. It is easy and inexpensive to produce, making it an affordable and accessible alternative to current catalysts on the market, which require materials that are expensive and in limited supply.

Their catalyst can also be used with any type of water, another factor that gives it an edge over current ways to generate hydrogen, such as water electrolysis.

“There’s a scarcity of potable water and that’s the biggest problem with water electrolysis to generate hydrogen – you have to use clean water,” says Hamilton. “With this, you don’t. We take something that is dirty, that you can’t drink, and generate hydrogen and electricity in a fuel cell. And it spits out water you can drink.”

“You could turn oil sands tailings ponds into usable fuel while purifying the water. It sounds like it’s too good to be true, but it’s not,” adds Veinot.

In addition to the catalyst being a marked improvement on the current catalysts available, it also transforms what is typically an energy-intensive process into something that can be achieved with far lower temperatures and less energy input.

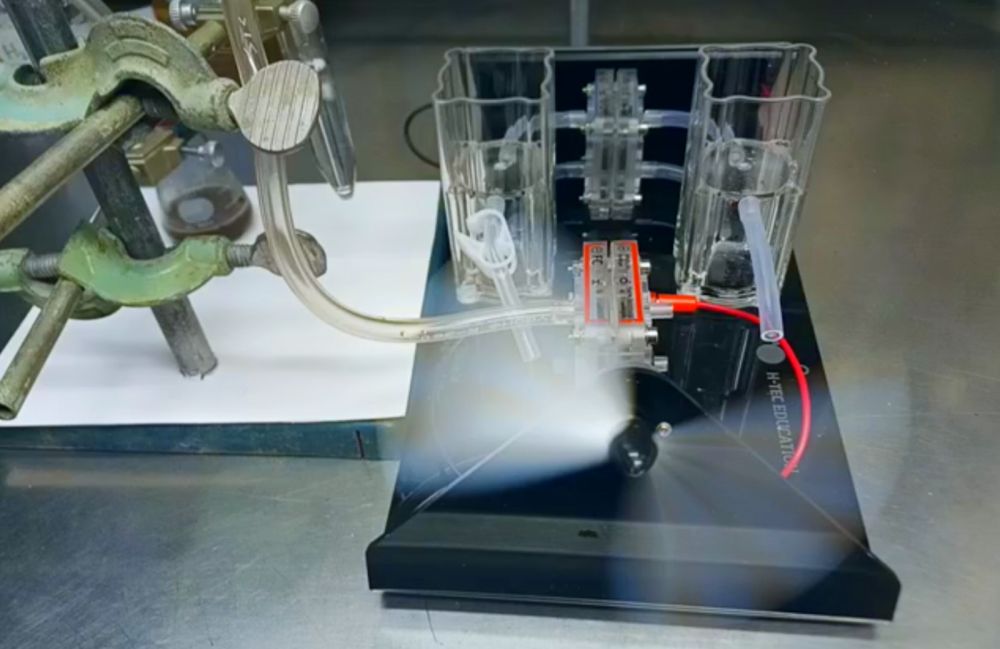

The new catalyst-driven process also results in little oxygen, making it less volatile than current methods. As Hamilton explains, when using a hydrogen fuel cell, the most common method to generate hydrogen is through water electrolysis. This process splits water into hydrogen and oxygen, separates them, then recombines them in the fuel cell to generate electricity.

“You mix hydrogen and oxygen and reach certain concentrations, that’s an explosive mixture. So you have to separate them to be able to use it safely. With our method, we sequester the oxygen without these expensive membrane separators that are normally used, and we can generate the hydrogen and have it go directly into the fuel cell. You don’t have to separate it,” says Hamilton.

“Think about having your garden hose providing you with the water that can be converted basically on demand to the fuel you want. It takes away transport, it takes away storage, it takes away negative explosive possibilities,” adds Veinot.

The researchers are initially looking to craft off-grid devices that could help remote communities or aid in disaster relief, when access to natural gas and potable water is an issue. They are envisioning an all-in-one system that is relatively compact and easy to use – “kind of like a SodaStream, but instead of squirting out CO2 to get your fizzy drink, it’s off-gassing hydrogen that goes into your fuel cell to generate your power,” says Hamilton.

“Off-grid solutions are the initial target because that’s where we can make the most impact.”

Applied Quantum Materials, a company co-founded by Veinot, is incubating Dark Matter Materials, a new company co-founded by Stryker and Hamilton to commercialize the new catalyst and method. Dark Matter Materials has already received interest from the local energy and agricultural sector, as well as from several multinational companies based in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

“We’re in a unique circumstance in Alberta in that Edmonton is going to be a hydrogen hub. The University of Alberta has a history in energy involvement, and the chemistry department has a history of involvement with energy with respect to the oilsands,” says Veinot. “We now have a pivotal opportunity to push this forward to the next level.”

Source: University of Alberta