Hydrogen fuel cells convert hydrogen to electricity with water vapour as the only by-product, making them an attractive green alternative for portable power, particularly for vehicles. However, their widespread use has been hampered in part by the cost of one of the primary components. To facilitate the reaction that produces the electricity, the fuel cells rely on a catalyst made of platinum, which is expensive and scarce. A catalyst using iron instead of platinum could enable greater use of the technology.

Platinum responsible for 60% of the cost

Lead researcher Professor Anthony Kucernak, from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial College London, said: “Currently, around 60% of the cost of a single fuel cell is the platinum for the catalyst. To make fuel cells a real viable alternative to fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, for example, we need to bring that cost down. Our cheaper catalyst design should make this a reality, and allow deployment of significantly more renewable energy systems that use hydrogen as fuel, ultimately reducing greenhouse gas emissions and putting the world on a path to net-zero emissions.”

All iron dispersed as single atoms

The team’s innovation was to produce a catalyst where all the iron was dispersed as single atoms within an electrically conducting carbon matrix. Single-atom iron has different chemical properties than bulk iron, where all the atoms are clustered together, making it more reactive.

Method can be used for other catalysts

These properties mean the iron boosts the reactions needed in the fuel cell, acting as a good substitute for platinum. In lab tests, the team showed that a single-atom iron catalyst has performance approaching that of platinum-based catalysts in a real fuel cell system. As well as producing a cheaper catalyst for fuel cells, the method the team developed to create could be adapted for other catalysts for other processes, such as chemical reactions using atmospheric oxygen as a reactant instead of expensive chemical oxidants, and in the treatment of wastewater using air to remove harmful contaminants.

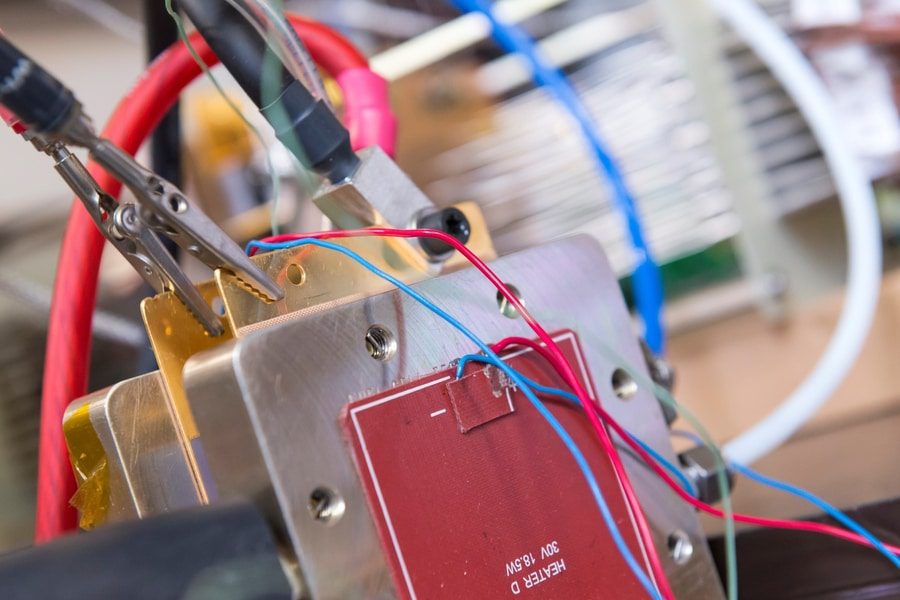

Commercial fuel cells

The team collaborated with UK fuel cell catalyst manufacturer Johnson Matthey to test the catalyst in appropriate systems and hope to scale up their new catalyst so it can be used in commercial fuel cells. In the meantime, they are working to improve the stability of the catalyst, so it matches platinum in durability as well as performance.

‘High loading of single atomic iron sites in Fe–NC oxygen reduction catalysts for proton exchange membrane fuel cells’ by Asad Mehmood et al is published in Nature Catalysis.